Cusco, Peru

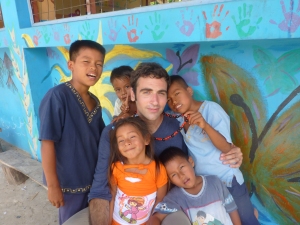

As mentioned in the previous post, the week spent at Yanapay was the first time during our trip that we felt like we had a job. Most likely, that’s because it was the first time that we had a boss micromanaging us. At Yanapay, we were not given the flexibility to run our program, but instead had to try to fit pieces of our curriculum into the rigid structure of the school (look at this cultish smock Luke had to wear, for example). We were successful in teaching some of the elements of our program and the kids were given the chance to perform at the end of the week, but inevitably we decided to stay with Yanapay for only 1 week instead of the 2 that we had originally signed up for.

Yanapay is a social project run entirely by a 37 year old local Cusqueno by the name of Yuri. The main outreach program is the after-school program which is home to about 100 local children ages 5 to around 12. The other outreach program is the cultural center which works more with the teenagers, adults and most ideally the parents of the children in the school program. Both are entirely self sustained by a restaurant in the city center and a hostel, whose income is funneled directly back into the project. That way the schools don’t need to solicit donations from the volunteers or rely on overseas sponsorship. Being one of the only organizations in Cusco that allows volunteers to give their time for free naturally attracts a lot of participants that there were.

During the first few hours of the day we were told to lead art class with the oldest batch of kids. We were teamed up with a man named Neil who was a middle aged manager for the Renewable Energy sector within the California government. He was there with his wife and 2 teenage children and had plans to hike the Incan Trail to Macchu Picchu the following week. Neil and his family had the best of intentions but had absolutely no preconceived notion of how they could contribute as volunteers and unfortunately none of them spoke any Spanish. We did our absolute best to accomodate Neil’s suggestions while sticking to our program; for example we would be in the middle of explaining a rhythmic concept when Neil’s eyes would light up and he’d say something like, “Hey! Let’s draw squiggles!” We would then draw squiggles for twenty minutes before resuming the rhythmic exercize.

Most of the volunteers show up at Yanapay without much of an idea of what they are going to do there, so they donate their presence to whatever task needs to be done. Usually they kill time by passing out paper and crayons or sitting in a circle and playing telephone. For me and Luke it isn’t really satisfying to work with the kids in this manner because up to this point we’ve tried really hard to create a program that is both educational and entertaining.

There was one other volunteer who also showed up with a pre- established program and we felt he had an interesting story. Joe from the UK has been living in Australia for the past few years as a sort of de facto music therapist. He works in a juvenile prison and is paid to run the prison wide radio station. He is a rapper and the kids get the opportunity to express themselves through hip-hop. Apparently the idea of being a rapper is extremely enticing to these young convicts and several of them have continued pursuing a rap career upon release. Sometimes Joe is contracted to do different sorts of awareness campaigns at the prison and some of them are really funny. For instance, one time he had to write a track about Hepatitis B. The teenagers were completely resistant at first until Joe had convinced them that Hep B is iike a gangsta with a body count. The rap ended up being a smash hit and they even made a music video about “Hep B, drivin down the blood stream, takin out the enemies.” The name of the song was “Heb B (You don’t wanna mess with me).” Joe had a similar program to ours in that he has been travelling around the world working with youth to use music as self-expression. Only instead of a banjo and mandolin he is equipped with portable speakers, a mic, laptop and mini piano.

After art class, all of the kids gather close for an exercise that is called the circle of expression. Yuri runs the show and discusses with the kids whatever topic he deems relevant that day. During one of these sessions there was a new student of about 7 years old with a physically deformed hand. As an introduction, Yuri called the child to the center of the circle and in front of an audience of about 90 proceeded to ask him about his likes and dislikes. After about 5 minutes Yuri lifted the diminutive hand of the shy little boy and presented it everyone. The rest of the assembly was spent discussing the deformed hand and how even with 2 fingers the boy was still able to write (with his other hand). He then went around the room asking the children and volunteers to bring to light any sort of disability that they might have. It was an interesting way to deal with the situation, to be so open and raw about it. I was a little worried that the child was going to be humiliated but he actually seemed to handle it perfectly fine and who knows maybe Yuri’s method will help to prevent the other kids from teasing him about it.

The remaining hour of the day is “family time.” At this point the kids are divided depending on their age group and are expected to learn about a specific topic and at the end of the week present about it in an artistic form. This week we were told to teach about Buddhism, an interesting topic for a community that is so devoutly Christian. Ultimately they are going to spend 3 weeks exploring Buddhism but during our week we were to teach only the story of Siddhartha Gautama. Luke and I were split into different groups and had to write and present two different songs. I think it’s fair to say that when it comes to writing latin pop/bluegrass crossover music, Luke and I are better as a duo but I’ll let the songs speak for themselves. We are uploading the videos tonight or tomorrow and will post them right here when they are finished.

After finishing up at Yanapay we decided to visit the #1 tourist destination in South America, Machu Picchu. We hadn’t really done much site seeing in the Cusco area up until that point because of how expensive it is to do anything that is considered touristy. For example, in order to enter any of the museums or ruins you have to buy a pricey “tourist ticket” that gives you access to everywhere but expires in 10 days. You are not allowed to pay an independent entry fee at any of the sites. As a way to beat the system and save a whopping $20 we decided to take a bus and then hike 3 hours to Macchu Picchu rather than take the train. This was the most terrifying journey of Luke’s life. We travelled in a crowded van for 8 hours on a windy, single lane road that had been dynamite-blasted into the side of a mountain, of course with no guard rail. I get car sick even on the straightest of roads so I was doped up on knock-off Peruvian Dramamine and didn’t really see what was gong on. As Luke recounts, “we were speeding at 50 mph, skidding out to avoid huge rocks that had fallen into the middle of the road. The driver, who was trying to impress 2 Colombian girls in the front seat, was screaming “adventure!!” while the guy behind me was praying and everyone else was screaming.”

We arrived to our destination alive, albeit shaken up. Machu Picchu itself is a spectacularly preserved and interesting site but the experience reminded us both of Disneyland. Long queues, single file lines through the buildings, loud American voices, pushing and shoving, etc.

The highlight of this trip was the unexpected, last minute dash up Mt. Machu Picchu, the peak overlooking the ruins. Most people, for some reason, get up at 4am to line up at Wayna Picchu, a much smaller peak that has maxes out it 500-person limit by 6am every day. We woke up much to late to do this, and so as a consolation decided to scramble up Machu Picchu. It turned out to be magnificent.

Unfortunately for us, we had chosen to go on what has been described as the busiest weekend of the year. That Friday had been Inti Raymi, the outdoor theatrical reenactment of an Incan ritual. It occurs on the winter equinox each year and is viewed by thousands of people from all over the world. Our vantage point was so far up that the actors looked like tiny ants but we were given the chance to absorb the enormous scale of the production.

We are way behind on blog posts, so we will put on a full court press to catch up on the stories of the School for Blind Children, Casa Hogar Garriones (an orphanage), and where we are now, Camino de Solidaridad, which is by far the most interesting and poignant chapter of our journey to date.

Reply

Reply